Seoul and Tokyo are once again battling over the sovereignty of Dokdo. The clash happens almost every year, as politicians and activists on both sides fiercely stake their claims.

Despite the nationalist sentiment which the issue arouses here (and among right-wingers in Japan), the validity of either side`s arguments is often obscured by the passion of the conflict.

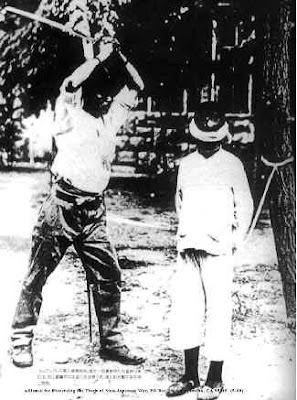

The Dokdo dispute is a centuries-long argument between the two countries; each cites historical documents and legal precedent to bolster their cases. For the Koreans, Dokdo is an integral part of the nation`s identity and a symbol of their resistance to past Japanese oppression.

For the Japanese, Takeshima, as they call it, is a piece of land that has been illegally taken away from Tokyo. Especially for the right-wingers, reclaiming Dokdo has been on the agenda since Japan lost the territory it had taken in the previous decades, following its defeat in World War II. They demand that Seoul bring the Dokdo case to the International Court of Justice, which Korea is extremely unlikely to agree to.

In both countries, politicians, academics and civic activists have been quite forceful in making their case. Korea refutes Japan`s arguments with its own legal and historical references, as well as the simple reality on the ground: Seoul physically controls Dokdo. What follows are some of Japan`s main arguments and Korea`s rebuttals:

Japan`s claims

Japan largely bases its legal claims on the Sept. 22, 1905 annexation of Dokdo by Shimane Prefecture. Tokyo asserted that, prior to that, Dokdo was "Terra Nullius," which is Latin for "land belonging to nobody." The concept traces back to the Roman Empire and subsequent legal decrees by European colonizers who usurped vast pieces of territory in their imperialistic expansions.

The term was taken to refer to uninhabited lands or those inhabited by "primitive people." The Terra Nullius concept has been applied to uninhabited areas like eastern Greenland, or inhabited places like Australia, where, despite the presence of Aborigines, British settlers took over the continent and stripped the Aboriginal people of their sovereignty. (Recent court cases in Australia have overturned many Terra Nullius arguments based on land ownership, thereby granting Aborigines some sovereignty.)

Japan appears to be arguing that Dokdo was never claimed by Korea and is therefore up for grabs. The Japanese say that Dokdo was never explicitly recorded as Korean territory in past records and that it is not visible on maps throughout history. The Korean maps and records offered by Seoul as evidence are simply referring to another island and not Dokdo, according to the Japanese.

They further claim that Koreans were never even aware of the existence of Dokdo until recently. Koreans who inhabited Ulleungdo 87 kiliometers away could not have known that Dokdo existed because it is not visible from there. Additionally, Koreans were primitive and lacked the technical skills to build boats hardy enough to navigate the waters between Ulleungdo and Dokdo - something the Japanese say they taught the Koreans when they set out to "modernize the area" during colonization.

Besides their claims regarding international law (the 1905 annexation), Tokyo also says that it had effectively "managed" the islands for centuries.

According to the Japan`s official Ministry of Foreign Affairs stance, "We firmly believe that Japan had established the sovereignty of Takeshima by the beginning of the Edo Period (1603-1867)."

Thus, Tokyo simultaneously asserts that it established sovereignty over Dokdo in the 17th century, and that Dokdo was Terra Nullius, thus justifying the 1905 annexation. Japan`s foreign ministry insists that Korea has been illegally occupying the islets and is violating international law.

Interestingly, the ministry`s 11-point outline of Japan`s claims to Takeshima includes an addendum warning its citizens not to enter Dokdo from the Korean side when traveling as tourists. This, they say, is to avoid giving the "wrong impression" that the Japanese people acknowledge that Dokdo is under Korean jurisdiction.

Korea`s rebuttal

Seoul`s claims to Dokdo date much further back than Tokyo`s. As has been reported by many sources, Korea`s first record of Dokdo dates back to the early 6th century when the Shilla Dynasty incorporated both Ulleungdo and Dokdo into their kingdom. For Korea, Dokdo was, is, and always will be Korean territory.

With regard to Japan`s Terra Nullius argument, Korea has responded by providing numerous maps and documents which show both Ulleungdo and Dokdo as part of Korean territory. To answer Japan`s protestations that many of the maps do not show the precise geographic locations of the islands, Koreans point out that maps drawn at the time (i.e., during the Joseon Dynasty) portrayed islands closer to the mainland to denote territorial ownership rather than exact location.

The claim that residents of Ulleungdo were not aware of Dokdo`s existence is also rejected. Contrary to what the Japanese say, one can indeed see the Dokdo islets from Ulleungo at a height of about 120 meters above sea level (this is proven by photographs taken from Ulleungdo). Since Ulleungdo is also a rocky island with an elevation as high as 985 meters, it is highly unlikely that its residents never saw Dokdo.

The notion that Koreans were too primitive to construct boats capable of sailing from Ulleungdo to Dokdo is also easily proven incorrect. Koreans point out that, throughout history (as far back as Shilla), boats had been regularly ferrying back and forth between the Korean peninsula and Ulleungdo. Also, the distance from Ulleungdo to Dokdo is much shorter than from the mainland. The claim that it was ultimately the Japanese who taught Koreans how to build a boat capable of traveling to Dokdo strikes most Koreans as ridiculously chauvinistic. Those Japanese are forgetting the fact that famous Korean seafarers such as Admiral Yi Sun-shin laid waste to the Japanese invading fleets with his own turtle ships, the world`s first armored warships, back in the 16th century. This humiliation of Japan occurred over a hundred years before it claims to have first known of Dokdo`s existence.

As for Tokyo`s insistence that the 1905 annexation was the last legal precedent regarding the matter of sovereignty, Koreans say that it was not a legal agreement, and that Korea`s political weakness at the time prevented it from adequately protesting Japan`s maneuver. Tokyo`s argument is that, since nobody opposed its seizure of Dokdo, that decision remains in force. But it must be noted that Japan basically controlled affairs in Korea to the extent that Korea`s foreign ministry was powerless to register a substantial complaint at the time. Furthermore, the fact that Japan did not bother to notify anybody of its annexation until one year later calls into questions the legality of the annexation, according to the view of most scholars and international legal precedent.

Finally, Koreans point out that Japan is contradicting itself by claiming that it "effectively managed" Dokdo in the 17th century and then declared Dokdo to be Terra Nullius in 1905. If Japan had already believed that it controlled the islets from so long ago, how could it then later claim that Dokdo was "land belonging to nobody"? In any event, evidently seeing the flaw in its logic, Tokyo`s foreign ministry recently omitted any references to Terra Nullius in its official claims. This weakens the argument that the 1905 annexation is Japan`s strongest legal case.

The Cairo Conference

Japan`s claims over Dokdo are also complicated by a very important event that occurred in 1943. The Allied powers during World War II convened in the Egyptian capital to address issues regarding Japan during and after the war. The "Cairo Declaration" was signed on Nov. 22 of that year, and outlined Japan`s fate once the Allies defeated Tokyo. It is a communique that is still recognized by the international community today.

Most pertinent to Korea, a stipulation in the declaration stated that "Japan will be expelled from all territories which she has taken by violence and greed (since the time of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95)."

After Japan`s defeat in 1945, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, which ruled postwar Japan, decreed that Ulleungdo, Jejudo and Dokdo would be excluded from Japanese territory. SCAP`s order, along with the precedent set by the Cairo Conference, are cited by Koreans to refute any current "legal" argument which Japan makes about Dokdo.

Furthermore, critics of the Japanese position point out that, if Dokdo is universally acknowledged to have been part of territory that was "seized by greed," a successful Japanese legal claim over Dokdo would give the country justification to again seize the entire Korean peninsula. This is a scenario which even the most rabid right-wing Japanese are not envisioning. For Japan to continue claiming territories which it took during its imperial expansion contradicts the terms of the Cairo Conference.

Japan`s Dokdo reality

At the end of the day, Japan`s only hope is to stir the waters enough to make the Dokdo debate an international issue. The goal is to somehow coerce Korea into bringing the dispute to the International Court of Justice. Despite the dubious merits of its case, Tokyo has nothing to lose in bringing the issue to the ICJ. It doesn`t hurt that Japan actually has a judge serving on the ICJ, while Korea is not represented. Seoul has consistently rejected Tokyo`s demands to take the case to the world court. As far as Seoul is concerned, Dokdo is Korean territory and not disputed land - precluding any justification for legal arbitration.

Seoul`s obstinacy regarding the ICJ demand forces Tokyo to resort to other means. That is why it has done things like declaring "Takeshima Day" in 2005, attempting hydrological surveys in 2006, lobbying international organizations to use "Liancourt Rocks" as the official name for Dokdo, and recently incorporating the Dokdo claim into the curriculum guide for middle school teachers. Rather than deliberately riling Koreans (though that is an inevitable consequence), Tokyo hopes that these kinds of moves will create international sympathy for its cause and create sufficient momentum for taking the case to the ICJ.

That tactic has so far been unsuccessful. Most countries - notably, the United States - refuse to take a stance on the Dokdo debate. This means that Japan`s only recourse is the faint hope that Korea will somehow decide to agree to an ICJ hearing. It should be pointed out that Japan is also embroiled in a territorial dispute with both China and Taiwan over the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu Islands in Chinese). Japan effectively controls the islands and refuses Chinese and Taiwanese demands to bring the case to the ICJ. Tokyo`s double standard here makes it that much less credible to Koreans.

The concept of "effective control" is important in assessing the Dokdo debate. Korea has been ramping up its efforts to physically control the islets. Some recent initiatives proposed by Seoul include constructing residential facilities for tourists and fishermen who visit the islets (except for the married couple and the 50 policemen stationed there, there is no other housing on Dokdo). Another proposal is to replace the policemen guarding the islets with armed forces, specifically marines.

In property disputes both large and small, an oft-cited line is that "possession is nine-tenths of the law." Originating in England, this states that physical possession supersedes most other arguments in ownership disputes. The concept has been applied in legal cases involving territorial disputes and even the argument over who was the rightful owner of Barry Bond`s 73rd homerun ball (a U.S. court ruled that the then-current possessor of the ball was the owner).

In the case of Dokdo, because Korea physically controls the islets, it cannot be forcibly removed from its control unless the ICJ rules against it. Since no other nation has supported Japan`s case to take the case to international court, Korea`s control over Dokdo is, and will indefinitely remain, the status quo. The only practical way that Japan could take over Dokdo right now would be through war (a war Tokyo would have to start by invading the islets). The reality for Japan is that, barring a complete collapse in the present Korean position, retaking Dokdo will be extremely difficult.

Despite the nationalist sentiment which the issue arouses here (and among right-wingers in Japan), the validity of either side`s arguments is often obscured by the passion of the conflict.

The Dokdo dispute is a centuries-long argument between the two countries; each cites historical documents and legal precedent to bolster their cases. For the Koreans, Dokdo is an integral part of the nation`s identity and a symbol of their resistance to past Japanese oppression.

For the Japanese, Takeshima, as they call it, is a piece of land that has been illegally taken away from Tokyo. Especially for the right-wingers, reclaiming Dokdo has been on the agenda since Japan lost the territory it had taken in the previous decades, following its defeat in World War II. They demand that Seoul bring the Dokdo case to the International Court of Justice, which Korea is extremely unlikely to agree to.

In both countries, politicians, academics and civic activists have been quite forceful in making their case. Korea refutes Japan`s arguments with its own legal and historical references, as well as the simple reality on the ground: Seoul physically controls Dokdo. What follows are some of Japan`s main arguments and Korea`s rebuttals:

Japan`s claims

Japan largely bases its legal claims on the Sept. 22, 1905 annexation of Dokdo by Shimane Prefecture. Tokyo asserted that, prior to that, Dokdo was "Terra Nullius," which is Latin for "land belonging to nobody." The concept traces back to the Roman Empire and subsequent legal decrees by European colonizers who usurped vast pieces of territory in their imperialistic expansions.

The term was taken to refer to uninhabited lands or those inhabited by "primitive people." The Terra Nullius concept has been applied to uninhabited areas like eastern Greenland, or inhabited places like Australia, where, despite the presence of Aborigines, British settlers took over the continent and stripped the Aboriginal people of their sovereignty. (Recent court cases in Australia have overturned many Terra Nullius arguments based on land ownership, thereby granting Aborigines some sovereignty.)

Japan appears to be arguing that Dokdo was never claimed by Korea and is therefore up for grabs. The Japanese say that Dokdo was never explicitly recorded as Korean territory in past records and that it is not visible on maps throughout history. The Korean maps and records offered by Seoul as evidence are simply referring to another island and not Dokdo, according to the Japanese.

They further claim that Koreans were never even aware of the existence of Dokdo until recently. Koreans who inhabited Ulleungdo 87 kiliometers away could not have known that Dokdo existed because it is not visible from there. Additionally, Koreans were primitive and lacked the technical skills to build boats hardy enough to navigate the waters between Ulleungdo and Dokdo - something the Japanese say they taught the Koreans when they set out to "modernize the area" during colonization.

Besides their claims regarding international law (the 1905 annexation), Tokyo also says that it had effectively "managed" the islands for centuries.

According to the Japan`s official Ministry of Foreign Affairs stance, "We firmly believe that Japan had established the sovereignty of Takeshima by the beginning of the Edo Period (1603-1867)."

Thus, Tokyo simultaneously asserts that it established sovereignty over Dokdo in the 17th century, and that Dokdo was Terra Nullius, thus justifying the 1905 annexation. Japan`s foreign ministry insists that Korea has been illegally occupying the islets and is violating international law.

Interestingly, the ministry`s 11-point outline of Japan`s claims to Takeshima includes an addendum warning its citizens not to enter Dokdo from the Korean side when traveling as tourists. This, they say, is to avoid giving the "wrong impression" that the Japanese people acknowledge that Dokdo is under Korean jurisdiction.

Korea`s rebuttal

Seoul`s claims to Dokdo date much further back than Tokyo`s. As has been reported by many sources, Korea`s first record of Dokdo dates back to the early 6th century when the Shilla Dynasty incorporated both Ulleungdo and Dokdo into their kingdom. For Korea, Dokdo was, is, and always will be Korean territory.

With regard to Japan`s Terra Nullius argument, Korea has responded by providing numerous maps and documents which show both Ulleungdo and Dokdo as part of Korean territory. To answer Japan`s protestations that many of the maps do not show the precise geographic locations of the islands, Koreans point out that maps drawn at the time (i.e., during the Joseon Dynasty) portrayed islands closer to the mainland to denote territorial ownership rather than exact location.

The claim that residents of Ulleungdo were not aware of Dokdo`s existence is also rejected. Contrary to what the Japanese say, one can indeed see the Dokdo islets from Ulleungo at a height of about 120 meters above sea level (this is proven by photographs taken from Ulleungdo). Since Ulleungdo is also a rocky island with an elevation as high as 985 meters, it is highly unlikely that its residents never saw Dokdo.

The notion that Koreans were too primitive to construct boats capable of sailing from Ulleungdo to Dokdo is also easily proven incorrect. Koreans point out that, throughout history (as far back as Shilla), boats had been regularly ferrying back and forth between the Korean peninsula and Ulleungdo. Also, the distance from Ulleungdo to Dokdo is much shorter than from the mainland. The claim that it was ultimately the Japanese who taught Koreans how to build a boat capable of traveling to Dokdo strikes most Koreans as ridiculously chauvinistic. Those Japanese are forgetting the fact that famous Korean seafarers such as Admiral Yi Sun-shin laid waste to the Japanese invading fleets with his own turtle ships, the world`s first armored warships, back in the 16th century. This humiliation of Japan occurred over a hundred years before it claims to have first known of Dokdo`s existence.

As for Tokyo`s insistence that the 1905 annexation was the last legal precedent regarding the matter of sovereignty, Koreans say that it was not a legal agreement, and that Korea`s political weakness at the time prevented it from adequately protesting Japan`s maneuver. Tokyo`s argument is that, since nobody opposed its seizure of Dokdo, that decision remains in force. But it must be noted that Japan basically controlled affairs in Korea to the extent that Korea`s foreign ministry was powerless to register a substantial complaint at the time. Furthermore, the fact that Japan did not bother to notify anybody of its annexation until one year later calls into questions the legality of the annexation, according to the view of most scholars and international legal precedent.

Finally, Koreans point out that Japan is contradicting itself by claiming that it "effectively managed" Dokdo in the 17th century and then declared Dokdo to be Terra Nullius in 1905. If Japan had already believed that it controlled the islets from so long ago, how could it then later claim that Dokdo was "land belonging to nobody"? In any event, evidently seeing the flaw in its logic, Tokyo`s foreign ministry recently omitted any references to Terra Nullius in its official claims. This weakens the argument that the 1905 annexation is Japan`s strongest legal case.

The Cairo Conference

Japan`s claims over Dokdo are also complicated by a very important event that occurred in 1943. The Allied powers during World War II convened in the Egyptian capital to address issues regarding Japan during and after the war. The "Cairo Declaration" was signed on Nov. 22 of that year, and outlined Japan`s fate once the Allies defeated Tokyo. It is a communique that is still recognized by the international community today.

Most pertinent to Korea, a stipulation in the declaration stated that "Japan will be expelled from all territories which she has taken by violence and greed (since the time of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95)."

After Japan`s defeat in 1945, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, which ruled postwar Japan, decreed that Ulleungdo, Jejudo and Dokdo would be excluded from Japanese territory. SCAP`s order, along with the precedent set by the Cairo Conference, are cited by Koreans to refute any current "legal" argument which Japan makes about Dokdo.

Furthermore, critics of the Japanese position point out that, if Dokdo is universally acknowledged to have been part of territory that was "seized by greed," a successful Japanese legal claim over Dokdo would give the country justification to again seize the entire Korean peninsula. This is a scenario which even the most rabid right-wing Japanese are not envisioning. For Japan to continue claiming territories which it took during its imperial expansion contradicts the terms of the Cairo Conference.

Japan`s Dokdo reality

At the end of the day, Japan`s only hope is to stir the waters enough to make the Dokdo debate an international issue. The goal is to somehow coerce Korea into bringing the dispute to the International Court of Justice. Despite the dubious merits of its case, Tokyo has nothing to lose in bringing the issue to the ICJ. It doesn`t hurt that Japan actually has a judge serving on the ICJ, while Korea is not represented. Seoul has consistently rejected Tokyo`s demands to take the case to the world court. As far as Seoul is concerned, Dokdo is Korean territory and not disputed land - precluding any justification for legal arbitration.

Seoul`s obstinacy regarding the ICJ demand forces Tokyo to resort to other means. That is why it has done things like declaring "Takeshima Day" in 2005, attempting hydrological surveys in 2006, lobbying international organizations to use "Liancourt Rocks" as the official name for Dokdo, and recently incorporating the Dokdo claim into the curriculum guide for middle school teachers. Rather than deliberately riling Koreans (though that is an inevitable consequence), Tokyo hopes that these kinds of moves will create international sympathy for its cause and create sufficient momentum for taking the case to the ICJ.

That tactic has so far been unsuccessful. Most countries - notably, the United States - refuse to take a stance on the Dokdo debate. This means that Japan`s only recourse is the faint hope that Korea will somehow decide to agree to an ICJ hearing. It should be pointed out that Japan is also embroiled in a territorial dispute with both China and Taiwan over the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu Islands in Chinese). Japan effectively controls the islands and refuses Chinese and Taiwanese demands to bring the case to the ICJ. Tokyo`s double standard here makes it that much less credible to Koreans.

The concept of "effective control" is important in assessing the Dokdo debate. Korea has been ramping up its efforts to physically control the islets. Some recent initiatives proposed by Seoul include constructing residential facilities for tourists and fishermen who visit the islets (except for the married couple and the 50 policemen stationed there, there is no other housing on Dokdo). Another proposal is to replace the policemen guarding the islets with armed forces, specifically marines.

In property disputes both large and small, an oft-cited line is that "possession is nine-tenths of the law." Originating in England, this states that physical possession supersedes most other arguments in ownership disputes. The concept has been applied in legal cases involving territorial disputes and even the argument over who was the rightful owner of Barry Bond`s 73rd homerun ball (a U.S. court ruled that the then-current possessor of the ball was the owner).

In the case of Dokdo, because Korea physically controls the islets, it cannot be forcibly removed from its control unless the ICJ rules against it. Since no other nation has supported Japan`s case to take the case to international court, Korea`s control over Dokdo is, and will indefinitely remain, the status quo. The only practical way that Japan could take over Dokdo right now would be through war (a war Tokyo would have to start by invading the islets). The reality for Japan is that, barring a complete collapse in the present Korean position, retaking Dokdo will be extremely difficult.