TOKYO ― These days the price of a standard civilian hit-job can run as high as $2 million. That’s not the price to get the job done―that’s the price if one of your underlings gets caught. The whole inflationary spiral started with one dumb yakuza stiffing McDonald’s on the price of a cheeseburger in Kyoto a few years ago.

The Yamaguchi-gumi, Japan’s largest organized crime group with 39,000 members and their notorious former underboss Tadamasa Goto (at left, from a 2005 video of a Yamaguchi-gumi celebration) are expected to reach a settlement this month with the family of a civilian killed in 2006. The surviving family members, represented by a group of 25 lawyers, filed the lawsuit last month, asking for ¥187 million in damages, or $2.4 million. (Tadamasa Goto was expelled from the Yamaguchi-gumi on October 14th, 2008).

A potential key witness to the murder was extradited from Thailand on Thursday and arrested on the plane back to Japan―on charges of driving without a license―by Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department detectives, who were waiting on the plane. The police also plan to question him about the killing and, of course, his lack of respect for Japan’s rules of the roads.

The arrest has made all parties involved with the murder anxious to sweep the case under the table. Goto, former head of the disbanded Yamaguchi-gumi Goto-gumi, who has never faced any criminal charges for ordering the hit, is desperate to avoid being tried in civil court, and said to be willing to cut a deal. However, it’s the current “CEO” of the Yamaguchi-gumi, Shinobu Tsukasa shown at right, who has the most to lose. At the time of the murder, he was in jail on gun possession charges, had no knowledge of the plan, and did not approve it, is not very happy to be cleaning up the mess. He doesn’t want to pay for a crime he didn’t commit or condone. Naturally. The whole thing is bad for business and terrible PR. It really damages the Yamaguchi-gumi corporate brand. And if the lawsuit actually goes to court, it could be a very bad legal precedent for “Yakuza Inc.”

According to those involved with the case and police sources, in 2006 Kazuo Nozaki, a real estate agent, was in a legal dispute with a Goto-gumi front company over the property rights to a building worth ¥2 billion ($26,000,000) in the Shibuya ward of Tokyo. On March 5 of that year, three members of the Goto-gumi waited for Nozaki to walk down a street in Tokyo’s upscale Kita-Aoyama area, and then one allegedly stabbed him to death with a kitchen knife. Of the three assailants, only two have been caught; criminal charges of ordering the hit were never filed against Goto.

The first hearing in the civil suit is tentatively scheduled for this month but sources on both sides say a settlement for the full amount is already being proffered by the Yamaguchi-gumi. A Yamaguchi-gumi middle manager said, “We don’t want this case to go to court. It could set a bad precedent. If this lawsuit were Apple versus Samsung, we’d be Samsung.”

It is an unusual lawsuit. Police sources say it represents the first time Japanese yakuza bosses have been sued for crimes pre-dating the 2008 revisions to the Organized Crime Countermeasures Law (暴力団対策法) which made it possible to hold organized crime bosses responsible for the actions of their underlings in civil court, by essentially recognizing yakuza groups as corporations.

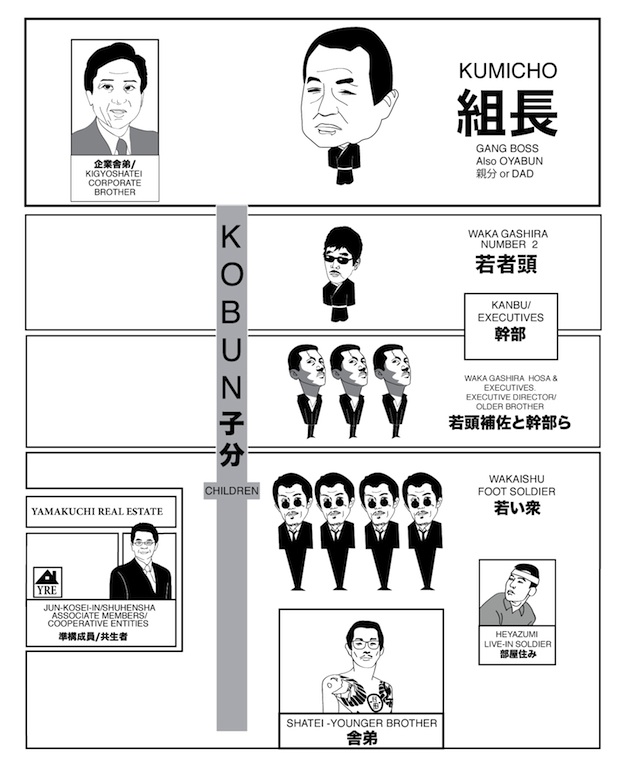

Former National Police Agency officer and lawyer, Akihiko Shiba, says that since it is very difficult to prove the criminal responsibility of the top yakuza bosses, lawsuits are one way of seeing justice is partially served. “The Organized Crime Countermeasure Laws are administrative laws, not criminal laws. The 2008 revisions made it clear that designated organized crimes groups function like a Japanese company, and therefore the people at the top have employer liability (使用者責任),” he explains. Since 2008, there have been at least three lawsuits against top yakuza bosses for damages by lower ranking members. All were settled out of court. “For the time being the use of civil lawsuits against top yakuza certainly has a deterrent effect on the management. The damages add up after a time,” Shiba says.

Others would agree.

These days, being a yakuza boss isn’t what it once was. In exchange for supreme status you get blamed for everything. In August of 2008, three months after the countermeasures laws went into effect, the Yamaguchi-gumi boss found himself dealing with one of his low-ranking underling’s unpaid McDonald’s tab. That’s because Japan’s approach to its major organized crime groups (there are 22) is to regulate rather than ban. They exist in the open with office buildings, business cards, and even company songs. The yakuza are Crime Incorporated. And in Japan, the CEO has to take responsibility for the screw-ups under his command. (To see how many people a boss has to worry about, see the org chart below.)

A 38-year-old Yamaguchi-gumi member had ordered burger combo at a drive-through in Kyoto. He picked up his order, but then claimed since his meal had gotten wet in the rain, he owed nothing, and drove off clutching his burger and fries. (It’s unclear whether it was a plain hamburger or a cheeseburger, accounts vary, but it was definitely not a happy meal.) Several days later, a bill arrived at the Yamaguchi-gumi headquarters in Kobe from a very angry McDonald’s manager. The organization paid.

The cheeseburger compensation was just the start of a series of legal headaches for the Yamaguchi-gumi and other yakuza groups. Over time, and with additional revisions to the laws, and broader interpretations by the courts, yakuza bosses now find “employer liability” increasingly burdensome. A boss can be held liable for any damages his cohorts inflict in the course of their business activities, including extortion.

There are a number of things about the lawsuit concerning Nozaki’s death that are different from anything preceding them. “If this case goes to court and the defendant loses, it could be a major setback for the yakuza,” says a retired police investigator formerly with the Tokyo Metro Police, who had over 20 years experience investigating organized crime. “It opens up a whole wave of possible lawsuits to crimes pre-dating the revisions. It may even be possible to sue in cases where the criminal statue of limitations is over. For the yakuza, at least the smart ones, this lawsuit is Pandora’s Box.”

Yakuza expert and the author of The Yakuza and The Nuclear Industry, Tomohiko Suzuki, concurs, “This lawsuit is big news in the underworld. It won’t stop the hits from happening but it will make people weigh the cost of killing an individual versus the money to be made.”

The Nozaki murder is still officially unsolved and who is ultimately responsible, criminally or civilly, has not been settled. The Goto-gumi member who police suspect of receiving the orders for the hit, Takashi Kondo, was assassinated in Thailand last year after an international arrest warrant had been issued. Dead men can’t be sued.

Tadamasa Goto, who is suspected but has never been charged with ordering the hits on Nozaki and Kondo, was kicked out of the Yamaguchi-gumi two years after the Nozaki murder on October 14, 2008, so his legal responsibility is unclear. Police officers call him “the father of Japan’s anti-organized crime legislation” because of his willingness to approve violent attacks on ordinary citizens generated so much anti-yakuza sentiment. He also jumped ahead of U.S. citizens in July of 2001 to receive a liver transplant at UCLA after making a deal with the FBI. Goto may no longer be part of the Yamaguchi-gumi, but he’s currently operating a new criminal gang under the moniker Goto Enterprises (後藤商事).

And the current Yamaguchi-gumi boss, Tsukasa, has never faced a criminal investigation for the murder because, as noted above, law enforcement sources believe (and underworld sources agree) Tsukasa never gave the order for the killing, never approved it, and was in solitary confinement when the job was done. He did finally approve the banishment of Goto, while he was still in jail, via his second in command.

A high-ranking member of the Yamaguchi-gumi, on background, feels that lawsuit this time is decidedly unfair. This member explains, “Mr. Tsukasa has never condoned the killing of a civilian. The Yamaguchi-gumi under Mr. Tsukasa forbids dealing in drugs, theft, robbery and violence against ordinary citizens―that’s not acceptable. Extortion and blackmail, that’s another issue. Anyway, one of the reasons the Yamaguchi-gumi finally kicked out Goto is because he continually violated even our lowest ethical standards. And now, six years after the fact, we have to clean up his mess again.”

Goto may pay his share of the damages but he is balking about paying the bill for his former godfather (Oyabun), Tsukasa. Goto has supposedly told his associates, “Who do you think put up the bail money for the old man in 2005? That was my ¥1 billion ($10 million) in cash! He kicked me out of the organization. And he still hasn’t paid me back. He can pay his damages out of what he owes me.” In the meantime, Goto is not strapped for cash. His defiant autobiography, Habakarinagara (Pardon Me But…), was a bestseller after it was published in 2010 and his new “business ventures” are reportedly highly successful.

Attempts to reach Goto for comment, including calls to his private cell-phone were unsuccessful. Sources close to Goto said he is hiding out in Cambodia until the lawsuit is settled.

While it’s certainly hard to feel any sympathy for Tsukasa, you can see why it’s a headache, at least, to keep homicidal sociopaths on the payroll. All you can do is fire them―if you can’t get them buried somewhere. And $2 million may seem like a drop in the bucket for a Japanese gang lord, but keep in mind with bail running around $10 to $15 million, it’s getting much harder to make a dishonest living these days.

Yakuza Organization Chart by @Marikurisato

Source: http://www.japansubculture.com/its-not-easy-being-a-yakuza-boss-part-1/